Unique data from the start of the melt season in the Arctic

Icebreaker Oden at an ice station, with a Helikite flying from the stern. Photo: Michael Tjernström

Icebreaker Oden at an ice station, with a Helikite flying from the stern. Photo: Michael Tjernström

An expedition that was characterized by excellent cooperation, curious polar bears, tough ice conditions and extensive collection of valuable data. Chief Scientist Michael Tjernström sums up the Oden expedition ARTofMELT, carried out in the Arctic Ocean during May and June this year.

– This has been the most harmonious of all the five expeditions I have participated in. Everyone had a great understanding of each other's activities and cooperated constructively. And cooperating instead of working against each other creates the conditions for more results for everyone. From my view as Chief Scientist, this was about weighing, for example, who would get access to the helicopter and when, as three different groups claimed this, while an additional group could not operate at all when the helicopter was in the air, says Michael Tjernström, Professor of Meteorology at Stockholm University.

Spring came late

The ARTofMELT 2023 expedition with the icebreaker Oden started early in the year, on May 7, which was more than two months earlier than is usually the case. The reason was that the researchers wanted to study the beginning of the melt season in the Arctic Ocean and the processes that affect the melting. Then it was important to be out in good time so that the transition from winter to spring and summer would not be missed. One theory the researchers had is that powerful inflows of warm and moist air from the south initiate the melting in the Arctic Ocean.

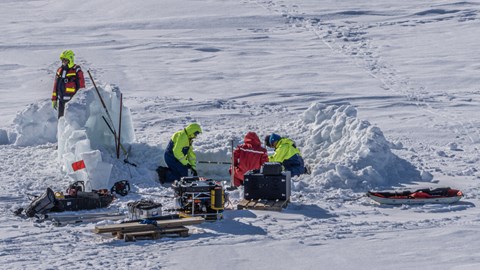

– There were unexpectedly few warm air episodes, and the transition to the summer's ice melting came late. But we captured the warm air episodes that came, one in the second half of May and the one in early June that led to the beginning of the melt season. In both cases, we had good control of the situation several days in advance and received the warm air under two ice stations with instruments on, in and under the ice. It also surprised us that "spring" began under the ice a couple of weeks before the air temperature went above the melting point, says Michael Tjernström.

The expedition was carried out by 38 researchers from 10 countries who worked on eleven different projects. The researchers collected data from the atmosphere and ocean and different types of ice and snow. Michael Tjernström says that his picture is that the researchers brought home the data they planned to collect and, in several cases, exceeded expectations. For example, both HELIPOD[1] and HELIKITE[2] could be flown more than expected, and more detailed measurements of the upper ocean were made than planned. In addition, a lot of data was collected when Oden was stationary at the same ice floe for several days, which happened twice. Regarding the meteorological observation program that he himself had been involved in and planned, Michael Tjernström was very satisfied.

– The geographical position is not really that important for processes in climate physics, it is the characteristics of the place that are important. The atmosphere has such great variability that it is usually impossible to find a certain place where a certain process occurs. Nearby terrain, Greenland or Svalbard, for example, can affect the atmospheric processes for specific places, so we avoid making measurements there. The important thing for us was to be inside the pack ice, preferably far from open water and, therefore, preferably far north. The atmosphere takes care of the rest!

Challenging ice conditions

A special aspect of the expedition was that it had no predetermined route. With the help of weather forecasts, it could be known a few days in advance when a hot air episode was coming, and then try to get Oden there. Through a unique collaboration with both the European weather centre ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) and the Norwegian weather service, the researchers had daily access to forecasts up to seven days in advance, and the quality of the forecasts was very good.

– Afterwards, we could conclude that it was a big challenge to navigate in difficult winter ice, therefore, we never got as far north as we had planned. Instead, we remained in the Fram Strait, where a difficult ice barrier blocked the way north. Between the ice floes, the pressure was also strong and varied a lot over the course of the day. We often saw how a planned route just closed before our eyes.

The many polar bear visits created strong impressions from the expedition but also became an obstacle to the researchers' ability to carry out measurements.

– During the second half of the expedition, we had over 35 visits from polar bears, which is a lot. We see polar bears on all expeditions, but usually only a few times. Now we had bear visits pretty much daily, sometimes more than once. This meant that we had to adapt the routines for working on the ice. Usually, all work on the ice is stopped when a polar bear appears, and everyone comes back on board. But towards the end, we had extra polar bear guards on the bridge to keep track of polar bears that were nearby but kept at a distance. That way, we could continue working on the ice but still quickly evacuate in case the bear changed its mind and started moving towards us.

Curiosity-based research

In what way can the research carried out at ARTofMELT 2023 be of benefit to society? Michael Tjernström explains that the underlying motivation for this type of research is primarily about increasing knowledge about a part of the climate system.

– We call it curiosity-based research; we simply want to know how it works! Without curiosity, there would be no research that could become applied in practice, only development based on pre-existing knowledge. Our results are freely available to all climate scientists, and the hope – and the goal – is that we will get better at predicting climate change and its effects in the Arctic. But we also hope our results contribute to better weather forecasts for the Arctic and for those who live and work there. Another area where we believe our results are important concerns the dynamics of the sea ice, how the ice develops and how this can be observed from satellite and making forecasts for this as well.