The hidden mercury cycle in the Arctic

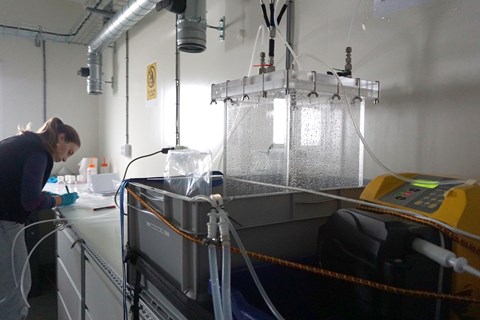

First attempt at deploying a 60L GoFlo! Its size and weight (once filled with water) require a crane to lift it overboard. Photo: Vicent Doñate Felip

First attempt at deploying a 60L GoFlo! Its size and weight (once filled with water) require a crane to lift it overboard. Photo: Vicent Doñate Felip

Makarov Basin, 1 September

I’m Ilaria Barale, a PhD student at Stockholm University and currently onboard the Swedish icebreaker Oden. I study how mercury moves between the ocean and the atmosphere. Right now, I’m writing this from the Makarov Basin, in the middle of the Arctic Ocean – and it feels a bit like sending a message in a bottle from a sea full of ice in all shapes and sizes.

Working on Oden

Here on board, I’m part of the Primary Production and Biogeochemistry work package (WP6), where we study how the phytoplankton community and the carbon cycle is affected by a changing Arctic. At the same time, I’m working on my own project within the Mercury Tracking work package (WP12), looking at at mercury cycling in the Arctic Ocean.

Sampling water and simulating sea sprays

Every day, we collect water samples from 8 meters depth, and occasionally from deeper layers using the CTD (an instrument that profiles the water column by measuring salinity, temperature, and depth). At ice stations, we also collect ice cores to understand the role of ice-associated biology in the Arctic Ocean.

I’m also running a sea spray chamber experiment—a setup that simulates the salty mist formed when bubbles burst at the ocean surface. This process produces sea spray aerosols: microscopic droplets suspended in the air. Such aerosols can carry substances from seawater, including mercury.

If mercury is released into the atmosphere through aerosols, that’s a transport pathway that isn’t currently accounted for in global mercury models. As sea ice retreats and waves and wind have more room to move, the amount of sea sprays may increase. That’s why we need to understand how important this pathway could be in the overall mercury cycle.

The GoFlo bottle and mercury isotopes

To trace where mercury comes from and how it transforms, I also collect water samples for mercury stable isotope analysis. We use a 60-liter GoFlo bottle, which we lower into the ocean at different depths. Deploying it for the first time was a bit stressful – so many things have to go right – but now it’s become a smooth part of the routine, thanks to the experienced Oden crew.

Isotopes are slightly different versions of the same element – in this case, mercury – with different mass but nearly identical chemical behavior. They act as chemical fingerprints, helping us trace where the mercury came from (natural sources, human activity, or something in between) and how it’s changed along the way.

Together with the sea spray experiments, the isotope data helps us build a more complete picture of mercury cycling in the Arctic Ocean.

Learning, sharing, growing

Being part of this Research School is not only about collecting data. I’m deepening my knowledge of the Arctic marine environment, its biogeochemical and physical processes, and its role in the global climate system.

This experience is helping me grow as a scientist – learning new sampling methods, collaborating across disciplines, and collecting unique data for my PhD project. Now halfway through the expedition, I feel inspired and excited. The Arctic Ocean is challenging, but it’s also a lab like no other.

So, this blog is my small message in a (GoFlo) bottle from the heart of the Arctic.

Ilaria Barale