Successful data collection in the Victoria and Nordenskjöld fjords

The icebreaker Oden in the Victoria Fjord during the North of Greenland 2024 expedition. Photo: Martin Jakobsson.

The icebreaker Oden in the Victoria Fjord during the North of Greenland 2024 expedition. Photo: Martin Jakobsson.

2024-09-02, leaving Victoria Fjord

As of September 1st, we have returned to the entrance of Victoria Fjord with IB Oden after spending 16 days in the fjord and the nearby Nordenskjöld Fjord to the north. Today, we depart from this area to re-enter the Lincoln Sea and begin our attempt to head northward, in line with our initial expedition plan. We are fully aware of the challenges and the risk of being forced to turn back and return to Pituffik if the sea-ice conditions prove too tricky. No ship has traversed the Lincoln Sea from south to north—or vice versa—for good reason. The first task on today’s agenda is an ice reconnaissance flight with the helicopter. I flew alongside Captain Erik Andersson and Expedition Coordinator Åsa Lindgren. If we cannot make it through the Lincoln Sea, we will be able to collect data from a completely unsampled region while returning south to Nares Strait.

The data collection in the fjord has been far more successful than I had dared to hope, even if the amazing armada of icebergs from the collapsed ice tongue efficiently put a stop to us at about 37 km from the fjord mouth. We have acquired over 1,520 square kilometres of multibeam bathymetry, a few hundred square kilometres larger than the island of Öland, Sweden’s second-largest island. We also collected sub-bottom profiles, midwater sonar data, and current information from the Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP) along with the bathymetry.

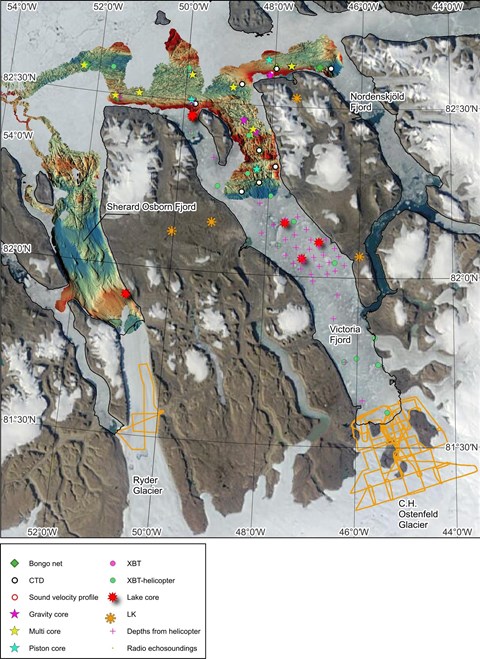

Our general operation mode involved mapping the seafloor at night, as the area is completely uncharted, and conducting data acquisition at stations during the day. Station work included retrieving sediment cores using piston, gravity, and multi-corers, collecting water samples, and measuring ocean properties with a CTD (Conductivity, Temperature, Depth). We deployed a “Bongo net” to capture living plankton for species study in these remote areas. We also carried out extensive work on land. The two helicopters were busy flying out our two geologists to study geology and place a set of seismometers along the eastern side of Victoria Fjord, and the teams were collecting driftwood and shrubs and drilling in lakes. Four lakes were successfully drilled using a Nesje piston. A major component of our program led by Nina Kirchner, my co-chief colleague, was using radar echo sounding from helicopter to measure the thickness of the C.H. Ostenfeld Glacier around its margin and the Ryder Glacier at its current grounding location. A total of about 700 km profile lines were flown.

The American group from the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping (CCOM) at the University of New Hampshire led by Larry Mayer, along with the team from KTH, used small remotely controlled vehicles to map icebergs. This began with taking Oden’s small workboat Munin close to an iceberg near Stephenson Island at the entrance of Victoria Fjord to support the remote-operated vehicles, Echoboat (CCOM/UNH) and Kuninganna (KTH). On a later occasion, Echoboat was used directly from Oden. It actually proved to be able to go over some thin ice that we thought was going to block its path. Additional activities with small boats we brought, Munin and Skibladner, include measuring methane along the shores and conducting seismic profiling and multibeam mapping.

In all, we have swept across the area and captured a huge amount of data that will help us understand this remote fjord and, in particular, the reason behind the complete collapse of C.H. Ostenfeld Glacier’s floating ice tongue in 2002.

Text by Martin Jakobsson, Co-chief Scientist, Professor at Stockholm University