Joy over rocks

Text by: Karna Johansson, expedition doctor

Imagine a researcher on a mountain. They weigh a piece of stone with a hand scale and look happier than the happiest angler. Stone, you might think, how can one find joy in that?

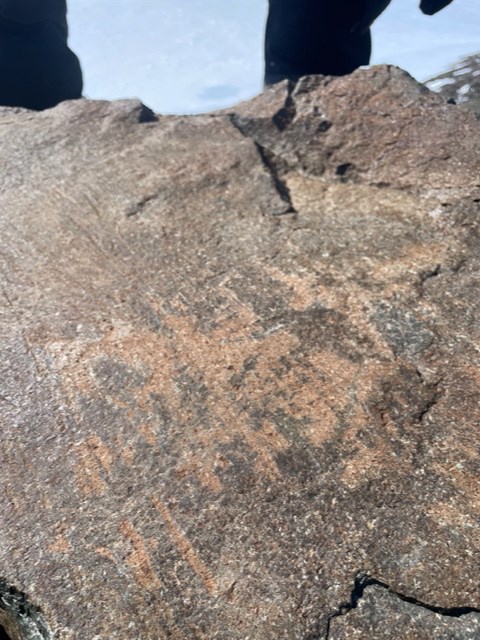

Nunataks, the peaks of the Antarctic mountains, are affected by the amount of cosmic radiation they are exposed to. The stone samples taken can be used to calculate how thick the ice has been throughout history. More sun, less ice. Knowledge of the historical extent of the ice sheet across Antarctica can contribute, among other things, to a better understanding of future climate changes.

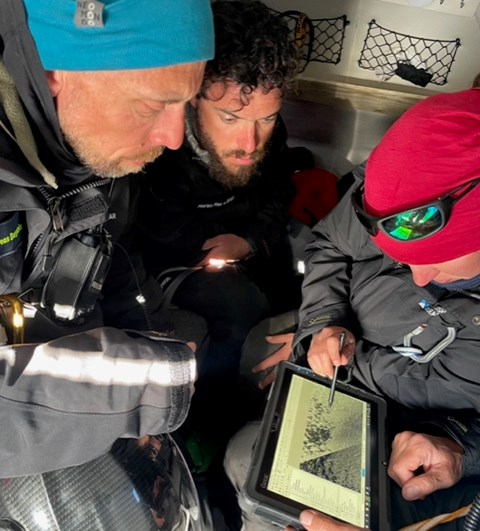

Research is a time-consuming process, and the one we are a part of here is no exception. In addition to all the preparations for getting here and back, analysing samples, processing data, and writing articles, the collection itself is time-consuming.

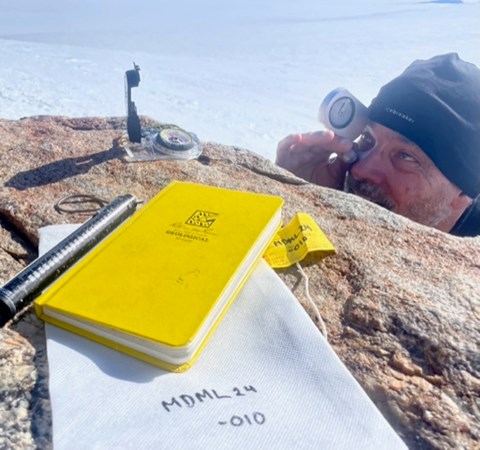

First, researchers must find a suitable location that meets criteria such as altitude, stone quality, and localisation; it may require many hours of driving and hiking to reach it. The location must then be precisely positioned with GPS, photographed, and mapped in relation to the horizon line. Only then is the sample taken, weighing more than a kilogram, using wedges, a hammer, or a percussion drill that must have warm batteries and sharp bits. Finally, the sample must be measured, placed in a specially labelled bag, weighed, and carried back to the snowmobiles. With this in mind, it is a bit easier to understand the joy of our researchers over a piece of stone.

And let me tell you, when you manage to detach that piece of stone just as you planned when drilling and driving in the wedges, a stone can be something to rejoice over!